When a baby is born small, it’s often attributed to genetic factors or maternal risk factors like poor nutrition or smoking. But a twin study led by researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital now find that slower transport of oxygen from mother to baby across the placenta predicts slower fetal growth, as well as a smaller brain and liver.

The study, published today in Scientific Reports (Nature.com) is the first to make a direct connection between birth outcomes and placental oxygen transport.

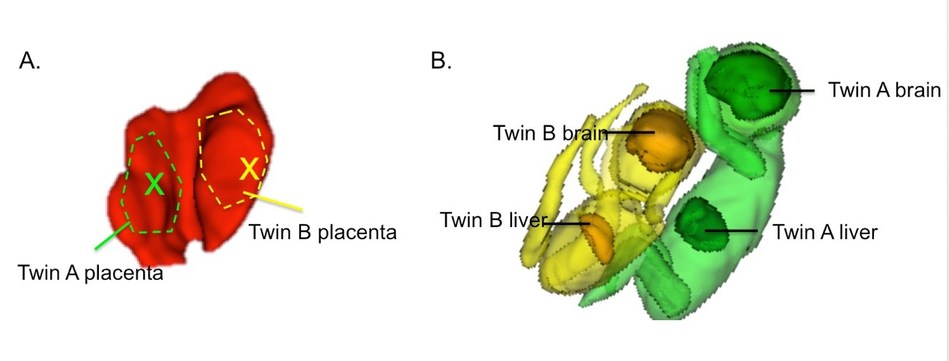

By studying identical twins, the researchers were uniquely able to control for both genetic factors and maternal risk factors. Although identical twins also share a placenta, it is divided into two separate compartments, and one may be healthier than the other.

P. Ellen Grant, MD, director of Boston Children’s Fetal-Neonatal Neuroimaging and Developmental Science Center, and Elfar Adalsteinsson, PhD at MIT have developed a noninvasive method that uses MRI to map the timing of oxygen delivery across the placenta in real time. Using this technique, called Blood-Oxygenation-Level-Dependent (BOLD) MRI, they showed that dysfunctional placentas have large regions with slow oxygen transport to the fetus.

“Until now, we had no way to look at regional placental function in vivo,” says Grant. “Prenatal ultrasound or routine clinical MRI can assess placental structure, but cannot assess regional function, which is not uniform across the placenta. Doppler ultrasound, the current clinical method of assessing placental function, measures blood flow in the umbilical arteries and other fetal vessels, but it cannot tell how well oxygen or nutrients are being transported from mother to fetus.”

Real-time placental oxygen mapping

In the new study, part of the NIH-funded Human Placenta Project, Grant, co-senior investigator Julian Robinson, MD, chief of obstetrics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), and their colleagues followed seven sets of identical twins all the way to birth, specifically tracking pregnancies in which one twin was smaller than the other.

At 29 to 34 weeks of pregnancy, the seven mothers underwent BOLD MRI for about 30 minutes. While they inhaled pure oxygen for 10-minute stretches, Grant’s team measured how long it took oxygen to reach its maximum concentration in the placenta, known as the time to plateau (TTP), and then how long it took for the oxygen to pass through the umbilical cord into the fetus and penetrate the brain and liver. Researchers led by Polina Golland, PhD, at MIT CSAIL used image-correction algorithms developed by MIT to adjust for fetal motion.

They found that a longer TTP in the placenta correlated with lower liver and brain volumes and lower newborn birth weights. TTP also correlated with placental pathology when placentas were examined after birth by placental pathologist Drucilla Roberts, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

Grant hopes her team’s work will be used to better understand pregnancy risk factors, develop a prenatal test for mothers in whom placental dysfunction is suspected and ultimately improve prenatal care. “Our next goal is to figure out what causes variation in oxygen transport in the placenta and identify a cutoff value that would be of concern in a pregnancy, including singleton pregnancies,” she says. “Then, we can think about potential treatments to improve placental oxygen transport, and use our methods to immediately assess the success of these treatments.”

Future directions

Grant believes placental oxygen transport is a prime example of how environmental factors can modify the DNA we all inherit. Future studies will investigate how placental oxygen transport affects fetal gene expression and specific measures of brain development and organ metabolism. These studies will use a special MRI coil to improve image accuracy, developed for pregnant mothers by collaborator Larry Wald, PhD, at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center. William Barth, MD, chief of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at MGH and Chloe Zera, MD, MPH, a BWH obstetrician, have also joined the team to guide the development of novel MR imaging strategies to improve the management of pregnant mothers.

“The placenta plays a key role in fetal development and maternal health,” says David Weinberg, project lead for NIH’s Human Placenta Project, launched by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. “Understanding how it functions is essential for developing interventions to improve the health of mothers and their infants.”

Jie Luo, PhD, and Esra Abaci Turk, PhD, both research fellows at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Madrid-MIT M+Vision Consortium, were co-first authors on the study. The research was funded by the NIH (U01 HD087211 and R01 EB017337) and the Consejeria de Educacion, Juventud y Deporte de la Comunidad de Madrid through the Madrid-MIT M+Vision Consortium. Luo, Abaci Turk, Grant, and co-authors Norberto Malpica, PhD, and Elfar Adalsteinsson, PhD (both of Madrid-MIT M+Vision Consortium) are co-inventors on a patent applications describing the MRI based method for measuring placental transport.

About Boston Children’s Hospital

Boston Children’s Hospital, the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, is home to the world’s largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center. Its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. Today, more than 2,630 scientists, including nine members of the National Academy of Sciences, 14 members of the National Academy of Medicine and 11 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators comprise Boston Children’s research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children’s is now a 415-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. For more, visit our Vector and Thriving blogs and follow us on social media @BostonChildrens, @BCH_Innovation, Facebook and YouTube.

SOURCE Boston Children’s Hospital